When Liam Conejo Ramos arrived back in Minnesota on Sunday, it was not just a child returning home. It was the end of a week that showed how quickly state severity can tip into outright overreach. The five year old had been detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers on January 20 in a suburb of Minneapolis, immediately after returning home from kindergarten. Together with his father, Adrian Conejo Arias, he was taken across the country to an immigration detention facility in Dilley, Texas.

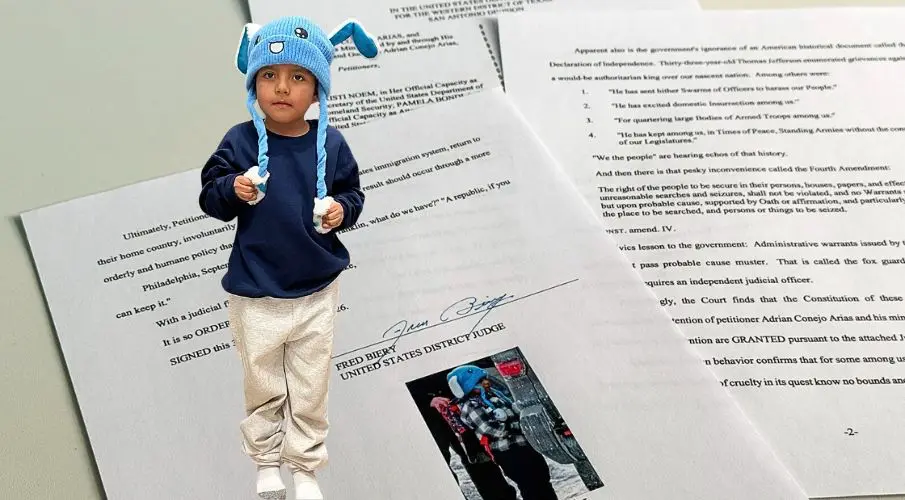

That a preschool child was handed over to bureaucracy in handcuffs triggered outrage nationwide. Images of the boy wearing a blue bunny hat and a Spiderman backpack, surrounded by armed officers, spread rapidly. They stood in stark contrast to the official statements with which the Department of Homeland Security tried to justify the incident. The child had not been deliberately detained, officials said, the mother had refused to take him, the father had insisted that Liam remain with him. This account contradicted statements from neighbors and school staff, who reported that the boy had been deliberately used to lure the mother to the door.

The turning point came through a federal court. Judge Fred Biery ordered the release of father and son and used unusually clear language. The case, he wrote, originated in a poorly conceived and inadequately implemented hunt for daily deportation numbers, even if that meant traumatizing children. The order, accompanied by Bible quotations and a photo of the boy, made clear how far administrative action had drifted from constitutional standards.

The return was accompanied by Joaquin Castro, who picked up Liam and his father from the facility in Dilley and personally brought them back to Minnesota. Immediately after Liam’s detention, contact was deliberately made with Congressman Joaquin Castro. This was not a coincidence, but part of an approach that can have an effect in the United States when state power spins out of control.

At the same time, lawyers were involved, documents prepared, jurisdictions clarified. The goal was to buy time before state power became a fait accompli. With precisely this approach of escalating cases early and making them politically visible, there had been repeated success in recent months, especially when children were affected. Forced deportations to Guatemala Guatemala were stopped, as was an attempt by the government to put Guatemalan children on planes and send them back to Central America within hours. Similar interventions prevented deportations of children from Honduras and exposed the worst individual fates that would otherwise have gone unnoticed. Our magazine is unfortunately full of such tragic cases and the struggle to help children – and of cases in which that help was successful. These cases show how narrow the line is between right wing populist state ideology and irreparable harm. It is deeply troubling how even a party like the AfD in Germany pursues this path and 25 to 27 percent of the population applaud approvingly. And it is precisely these stories that linger for a long time, because they make clear what happens when no one looks in time. During the flight, the congressman wrote the boy a letter. Liam had moved the world, he wrote, and no one should tell him that this was not his home. It was a personal gesture in a process otherwise defined by files, statutes, and jurisdictional deflection.

In front of the family’s house in Columbia Heights, neighbors gathered, brought balloons, and celebrated the return. Many did so not only out of joy, but out of concern for other children from the neighborhood who remain held in detention facilities in Texas. Parents showed photos of their own children and spoke of similar arrests without publicity, without images, without political pressure. Liam’s case had given hope, they said, but had also made clear how randomly attention is distributed.

Politically, the government stuck to its line. A spokesperson for the Department of Homeland Security once again emphasized the claim to enforce law and order and to detain and deport people without legal status. The boy’s father, the agency said, had entered from Ecuador in December 2024. His lawyer, however, points to an ongoing asylum proceeding that allows him lawful presence. The online docket of the immigration courts currently lists no further hearings.

What remains is more than an isolated case. A child became the face of a practice that otherwise unfolds out of sight. The return to Minnesota ends the detention, but not the questions. How many similar cases remain invisible because no camera is present. And what does it say about a state when a judge must intervene to allow a five year old to return to school. Liam’s path back home is complete. The political and legal reckoning is only beginning.

Updates – Kaizen News Brief

All current curated daily updates can be found in the Kaizen News Brief.

To the Kaizen News Brief In English