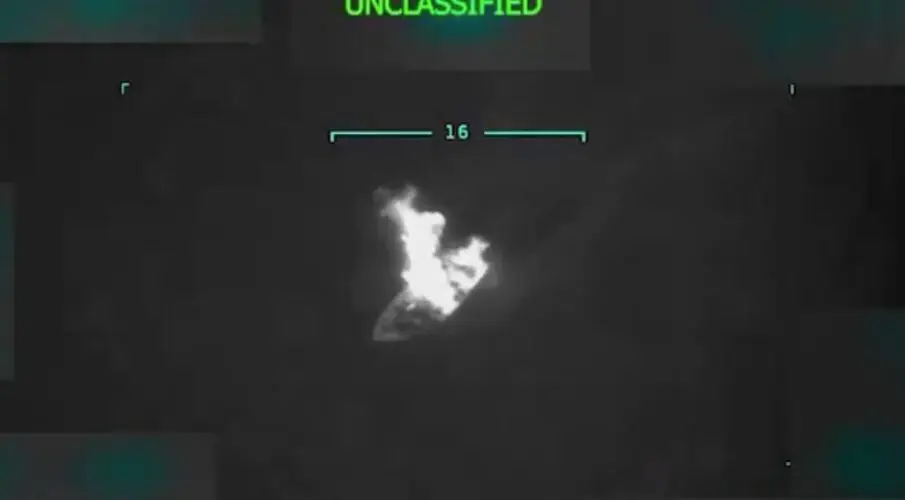

The image is brief and brutal: A small boat in international waters, a dot in the sea, seconds later a fireball. This freeze frame from a video of the U.S. Department of Defense shows the final moments of an operation that has now become one of the most sensitive cases of the Trump era. Eleven people on board, a U.S. aircraft in the sky, four missiles, in the end no survivor. And a central claim that is becoming increasingly fragile.

Before lawmakers, Admiral Frank Bradley, the then commander of the Joint Special Operations Command, explained that the boat that was hit had been on its way to a larger ship that was supposed to go to Suriname. There, according to the account, the drugs were to be transferred to the second ship. Suriname, a small country east of Venezuela, has been listed for years as a transit station in international drug trafficking. Bradley argued that the cargo could eventually reach the United States from there. That was sufficient, he said, to justify a lethal strike, even though at the time of the attack the boat was neither heading toward the U.S. coast nor aiming at any concrete destination in the United States.

Already at this point the logic completely falls apart. U.S. drug enforcement officials themselves point out that routes through Suriname primarily target European markets. Supply lines to the United States have for years run mainly across the Pacific. In other words: The specialists themselves say that this route statistically leads to Rotterdam, not to Miami. Research revealed the same fact, a ghost ship that apparently sails across the ocean only in Bradley’s imagination in order to relieve himself and Hegseth. Nevertheless, the attack is publicly sold as a protective measure for the United States, as the defense against an imminent threat.

At the same time, key actors in the government contradict each other in glaring ways. Secretary of State Marco Rubio stated back then shortly after the strike, speaking to traveling journalists, that the boat had been "likely on its way to Trinidad or another Caribbean country". President Donald Trump, on the other hand, appeared before the public and claimed that the strike had hit a boat that had been transporting "illegal drugs toward the United States" in international waters. Two versions, one objective, and both do not match the newly submitted scenario three, the Suriname story.

Rubio’s version does not withstand even basic logic. If the boat had truly been on its way to Suriname, he would have said exactly that. Instead, he presented a completely different story at the time and spoke of Trinidad or "some other Caribbean country". This evasive movement shows that Suriname was only later written into the script, not because it corresponded to the truth, but because a new explanation was needed. Rubio’s statement not only contradicts the established facts, but also reveals that the official line was subsequently bent into a lie.

Now to the next version: Trump claims in his post of September 2 that the U.S. military, acting on his personal order (so there were indeed orders, note of the editorial staff), struck a boat that he describes as part of the "Tren de Aragua" terrorist organization. He accuses the group of being responsible for murder, drug trafficking, human trafficking, and violence throughout the Western Hemisphere. According to his account, the boat was in international waters and was transporting illegal drugs "on the way to the United States". The strike had killed eleven "terrorists" without injuring U.S. soldiers. At the same time he declares the strike to be a warning to anyone who might want to bring drugs into the United States.

Added to this is another point that makes the situation even more explosive. Bradley admitted that the boat had turned around before it was hit because the people on board had apparently seen the American aircraft. That means: The occupants recognized the danger, changed their course, and evidently tried to evade or at least react. The U.S. military fired anyway. The first strike split the boat into two parts, two survivors clung to a piece of wreckage. Then came strike two, three, and four, the missiles that killed the last survivors and finally sank the boat.

According to Bradley’s account, the two men "waved into the air". He leaves open whether they surrendered, asked for help, or simply gestured in panic. Yet at exactly this point a military operation becomes a question of international law. Shipwrecked persons floating in the water and "requiring help and care", as the Pentagon’s own law of war manual puts it, may not be attacked. They must refrain from any acts of hostility, and precisely because of this they are protected. Anyone who kills them anyway crosses a red line that is not only morally but legally clearly drawn.

Hegseth on Sept 2nd Strike: "I stayed for probably five minutes or so after but at that point it was a tactical operation and I moved on to other things. A couple hours later, I was told there had to be a re-attack because there were a couple of folks who could still be in the fight, access to radios… I said, Roger, sounds good. From what I understood then and what I understand now, I fully support that strike. I would have made the same call myself"

Particularly questionable is that to this day no one has disclosed the exact orders that led to this operation. Lawmakers were told that Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth had made it unmistakably clear before the mission that the operation had to be "lethal". Bradley in turn explained that he understood the objective to be that all eleven people on board should die and that the boat should be sunk. At the same time a U.S. official emphasizes that there had been no explicit order to "kill everyone and show no mercy" which would be a formulation that is clearly illegal under international law and is completely contradictory. Exactly here a dangerous gap emerges: an operation that is effectively conducted as if there had been an order without mercy while officially insisting that no such order was ever issued. Anyone who wants to believe that might also believe that Trump deserved the Nobel Peace Prize or follow the example of FIFA and honor a man for his ongoing human rights violations at home and abroad.

That the government does not make the exact command chain transparent is more than a formality. It is an attempt to keep a lethal operation in a gray area, hard enough to kill everyone on board, but vague enough to be able to say in court that no one had been instructed to execute prisoners or shipwrecked persons. Anyone who argues like this leaves the realm of proper military responsibility and enters a zone in which words are subsequently bent so that they appear just barely defensible under criminal law.

Added to this is a detail that we have also researched. If neither military sensors nor subsequent image analyses can confirm a larger ship in range, the question arises whether the alleged rendezvous with a Suriname ship is anything more than a retroactively added explanation. A small boat was blown up, the survivors were deliberately killed, and now a story is told of an alleged connection whose material traces cannot be found.

For the Trump administration, this operation is part of a larger campaign in which military force against alleged drug boats has almost become a routine instrument. Many Republicans in Congress fundamentally support this line because it promises tough action against cartels and smugglers. But it is precisely the second strike of September 2, the moment in which two shipwrecked persons were killed one after another by multiple missiles, that has raised bipartisan doubts. The Senate Armed Services Committee has announced that it will investigate the events in detail. It is no longer only about whether a boat transported drugs. It is about whether the United States committed a war crime in international waters.

At the center of this is Hegseth’s role. Did the Secretary of Defense from the outset want to send a signal that would have the greatest possible "deterrent" effect and did he accept that everyone on board would die for that purpose? Or was it a commander who transformed a political desire into a military order that in practice left almost no room for retreat? The assertion that Hegseth only learned about survivors when they were already dead may be formally correct, but it does not answer the question of why an operation is planned in such a way that in the end no one remains who could even testify as a prisoner in court. Nor does it answer the question of how exactly the operational directive was formulated, because Bradley’s account has very little to do with reality.

That the U.S. government defends this case with the claim that an imminent threat to the United States had been averted appears, given the known facts, like a protective shield that not even the government’s own specialist agencies support. A boat that turns around after seeing an aircraft. An alleged connection to a ship that does not appear in any available image or sensor data. Smuggling routes that lead more toward Europe. Two shipwrecked persons waving into the air and three additional missiles that kill them.

In the end, an uncomfortable truth remains: If this operation passes without orders being disclosed, responsibilities clearly identified, and international legal standards consistently applied, it opens the door to a practice in which military force at sea knows almost no boundaries. That is why it is so important that this case does not fade away. It is not only about a night in September above the Caribbean. It is about whether international law still applies where a boat looks as small as a dot on a satellite image and a missile strike lasts only a few seconds.

Investigative journalism requires courage – and your support.

Support our work against right-wing populism, disinformation, and violations of human and environmental rights. Every contribution goes directly into our daily reporting – we operate without advertising, without subscriptions, without corporations, without political parties. Our journalism is meant to remain freely accessible. For everyone.

Independent – Critical – For Everyone

Thank you for making our independent work possible.

Updates – Kaizen News Brief

All current curated daily updates can be found in the Kaizen News Brief.

To the Kaizen News Brief In English

Das ist richtig übel und eine gelungene Recherche. Danke für die Arbeit, die ihr tagtäglich macht, es erscheint mir, 24 Stunden.

… das kann ich gut verstehen, wir empfinden es auch als extrem verstörend