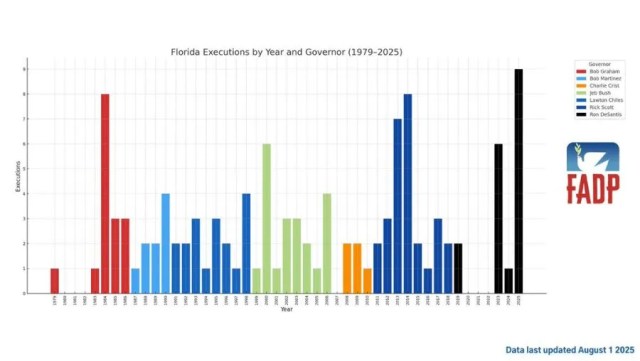

It is a scene that had become increasingly rare in the US for decades – and which now suddenly takes on symbolic power again: In the glaring light of a prison chamber, watched by guards and on the back of American society, a man dies in Florida from a lethal drug mixture. It is Edward Zakrzewski, 60 years old, whose last words are a sarcastic thank you to the state that kills him “cold, calculated, clean and efficient.” What sounds like a grim footnote in truth marks a historic turning point: In no other year since the reinstatement of the death penalty in 1976 has a governor of Florida executed so many people as Ron DeSantis in 2025.

The numbers speak for themselves: nine executions in just seven months, 27 nationwide – and the trend is rising. Florida has taken the lead in a macabre race that is catapulting the country back to a level many thought had been overcome. But this new wave of executions is no coincidence and also not a reflexive response to crime rates or social pressure. It is the result of political calculations, strategic communication – and a profound shift in the way state violence is handled. Ron DeSantis does not portray himself as an uncompromising enforcer by accident. In a political climate where “law and order” has become a core feature of Republican power, the governor uses the death penalty to demonstrate toughness – and to sharpen his own agenda against the influence of Washington. Since President Trump has called on prosecutors to seek the death penalty more often, conservative states like Florida have delivered the required numbers. DeSantis presents himself as a man of action: “There are crimes for which only the death penalty remains.” The message is clear – to his own electorate, but also to political rivals and the president.

But how is it decided in Florida who dies and when? The criteria are nontransparent, the process incomprehensible to outsiders. Criticism of arbitrariness has been known for years, but it seems to hardly slow down the pace of executions. The number of death row inmates remains high, proceedings are being sped up, even for inmates who have been waiting for execution for decades. It seems as if the state finally wants to create facts – regardless of the public debate. The reason the death penalty never really disappeared in the US has much to do with its symbolic value. Anyone familiar with the history of American justice knows: Executions are a tool of power, a ritual of social cleansing – and often a means of political positioning. States like Florida, Texas and Oklahoma top the statistics not because more crimes occur there, but because political majorities and strong governors want it that way. It is a kind of “execution federalism”: the decision over life and death is not a legal one, but a political one.

This dynamic also explains why the current wave of executions is not due to increased public support. On the contrary: Polls have shown for years that the majority of Americans are skeptical of the death penalty, many states have suspended or abolished it. Yet in election campaigns, during media escalation, it remains a sharp weapon. Those who carry out the death penalty demonstrate capacity for action – and steal the show politically from no one.

What is often overlooked: The staging of the execution is as much a part of the political strategy as the decision itself. Every press photo, every report of an execution signals: “Order is being restored here, there is control here, toughness rules here.” For many relatives of victims, this is a relief – and yet the question remains as to what is really gained. Critical voices, including human rights organizations, churches, and anti-death penalty initiatives, continue to protest. They speak of “state arbitrariness,” call for transparency, and criticize the lack of control over the last means of state power. Thousands of petitions are submitted, vigils held, pleas for clemency delivered directly to the governor’s office – mostly unsuccessfully. The political symbolism is stronger than compassion.

While Europe has long since said goodbye to the death penalty and even in the South of the US the number of executions has decreased sharply in recent decades, states like Florida steadfastly stick to the old system. The result: The USA ranks year after year in the sad statistics alongside countries such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, or Egypt. China is estimated to be in the lead, but there are no precise figures – the USA, on the other hand, documents every execution publicly. The international reputation suffers, but domestically that seems to hardly matter. On the contrary: Executions are politically exploited to demonstrate toughness against criminals – a “culture war” against supposed weakness.

What disappears in the statistics are the human tragedies behind each sentence, the doubts, the mistakes, the imponderables of the American penal system. The death penalty is often not the result of swift and certain justice, but of protracted proceedings, sometimes grave miscarriages of justice, and psychological attrition for perpetrators and victims’ families alike. The fact that in Florida two men have been waiting for their execution for over forty years illustrates the Kafkaesque side of the system. Execution becomes the endpoint of an odyssey of hope, rage, fear, and resignation. While opponents of the death penalty pray, protest and hope that reason will triumph over revenge, the governor has the last word. Ron DeSantis has signed off on two more executions. For activists like Suzanne Printy it is clear: “He is the one person who could stop this.” But the political stage demands toughness – and toughness is what it gets. The death penalty in Florida in 2025 is more than a legal instrument. It is a statement, a signal, a weapon in the political struggle for power. To understand it, one must read more than statistics. One must ask who benefits – and who lives in its shadow.

Investigative journalism requires courage, conviction – and your support.

Furchtbar.

Ja, es gibt unglaublich unbeschreiblich grausame Verbrechen, wo man denkt, der Täter verdienen den Tod.

Ich verstehe auch die Angehörigen der Opfer, die den Täter tot sehen wollen.

Aber gefragt man due Meisten einige Zeit später, hat es Ihnen nicht den Frieden gegeben, den sie sich erhofft hatten.

Lediglich „die Person kann nie wieder Jemanden etwas antun“

Aber wer sind wir, dass wir uns auf das Niveau des Täters herab gegeben und über Leben und Tod entscheiden?

Und dann noch die, gar nicht so wenigen Fälle, wo es Fehlurteile waren.

Wo ein Unschuldiger, zumindest an dem Verbrechen, hingerichtet wurde.

Tot ist tot.

das kann man nicht mehr rückgängig machen.

Wo ist da die Pro-Life Bewegung?

Ach ja, die tritt ja nur auf, wenn es um ungeborenes Leben geht….

Ich verstehe auch Angehörige, doch eine gesunde Gesellschaft, kann und darf so etwas nie akzeptieren.