The 1.5 degree mark was never a symbolic number. It was a red line. Enshrined in Paris in 2015, at the urging of those states that already knew they would pay first - with land, with harvests, with human lives. Ten years later, that line has effectively been crossed. For the first time, a three year period through 2025 has breached the threshold of 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels. And as the data tightens, the political will to truly cut emissions is fading. Robert Watson, former chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, puts it without softening the blow: “Climate policy has failed. The landmark 2015 Paris Agreement is dead.” What sounds clinical describes a turning point. The 1.5 degrees were meant as a shield - against extreme weather, against runaway warming, against irreversible tipping points in the Earth system. Today, many researchers openly say those tipping points are closer than long assumed.

So far, climate change has unfolded in waves, accelerated but largely gradual. But concern is growing that the next phase may no longer be incremental, but abrupt. Tim Lenton of the University of Exeter warns that we are approaching several tipping points in the Earth system that could transform the world with devastating consequences for people and nature. The notion that temperatures could simply be “turned back down” after a temporary overshoot increasingly looks like wishful thinking under these conditions.

The jet stream is one of the decisive control factors of our weather. At altitudes of five to seven miles, a band of powerful winds stretches thousands of miles around the Northern Hemisphere. It forms where icy polar air meets much warmer air masses from the subtropics. From this temperature contrast emerges a fast west to east current that arcs around the globe. This high altitude band acts as a steering system for low pressure systems. It determines where storms move, where rain falls, and which regions remain dry. The western United States, southern Europe, the Mediterranean - all depend on these upper winds transporting storm systems in their direction. If this transport shifts, entire precipitation patterns shift with it.

With global warming, this very mechanism is under pressure. The Arctic is warming faster than many other regions. As a result, the temperature difference between the North Pole and the mid latitudes shrinks - the very force that keeps the jet stream strong and stable. If that difference weakens, the wind band can slow, wobble more strongly, or shift farther north. The consequences are felt on the ground. When the waves of the jet stream grow more pronounced, high or low pressure systems linger over one region for longer. Heat waves stretch on for weeks. Drought intensifies. Heavy rain can stall. Regions that depend on passing winter storms receive less precipitation. Weather patterns become slower - and more extreme.

The graphic makes this visible. Over North America, a colored band shows wind speed at altitude. Blue and green mark slower currents. Yellow, orange, and red indicate the strongest winds - this is the core of the jet stream, with speeds of 90 to 185 miles per hour. The curved structure shows the typical meanders of the wind band. The more pronounced these bends, the greater the contrasts on the ground: on the southern side, extreme heat can lock in; on the northern side, cold air plunges far south. If the jet stream shifts permanently, it is not merely a wind band at high altitude that changes. The entire weather pattern between North America, the Atlantic, and Europe - down into the Mediterranean - is altered. Regions that still benefit from regular winter storms could become drier. Others may face more frequent blocking highs or intense precipitation events. The jet stream is the steering system of Northern Hemisphere weather. If the global temperature system shifts, this system reacts. And with it, the stability of entire climate regions.

The warning signs are already visible. Heat deaths in India, Africa, and the Middle East are rising sharply. In the United States and worldwide, forests are burning on an unprecedented scale. Tropical storms and extreme rainfall are causing ever greater damage. NASA researcher Bailing Li presented internal data showing a dramatic increase in the intensity of extreme weather events over the past five years. The International Chamber of Commerce estimates the economic damage from extreme weather over the past decade at more than two trillion dollars. One fifth of the world’s population has been directly affected.

The past three years have been the hottest since records began. 2023 and 2025 came in just under 1.5 degrees, 2024 at 1.55 degrees. Formally, the Paris threshold is defined as a long term average over about 20 years to smooth natural fluctuations such as El Niño. But two studies already concluded last year that the world has likely already crossed this critical mark. Without a radical course correction, warming will continue to accelerate. James Hansen, whose 1988 testimony before the US Senate brought the issue to global front pages, considers two degrees by 2045 possible if emissions remain high. The climate system is caught in a vice: greenhouse gas emissions remain elevated, while natural carbon sinks are weakening. 2024 recorded the largest annual increase in CO2 concentration ever measured.

For decades, nature absorbed about half of the CO2 emitted by humans. Forests grew faster, oceans stored carbon dioxide in the deep. But these buffers are reaching their limits. The oceans are becoming more stratified, their capacity to absorb CO2 declining. Forests suffer from heat and drought. Several studies report an unprecedented weakening of land based carbon sinks in 2023 and 2024, fueled by a global doubling of extreme wildfires within two decades. African rainforests, once major carbon stores, temporarily became sources of emissions themselves.

A collapse of the Amazon would release billions of tons of CO2. Thawing Arctic permafrost releases methane, a highly potent greenhouse gas. Researchers see this as a critical amplifier in scenarios where the 1.5 degree threshold is exceeded. Johan Rockström of the Potsdam Institute speaks of “cracks in the resilience of Earth systems.” Nature has so far absorbed part of our abuse. That is now ending.

The oceans are also sending clear signals. They have never been as warm as in the past three years. Off northwestern Europe, temperatures in spring ran up to seven degrees Fahrenheit above normal. Tropical waters are heating up, cyclones intensifying, coral reefs dying. Researchers believe tropical reefs may already have crossed a tipping point. By mid century, they could largely disappear - with massive consequences for marine ecosystems and fisheries.

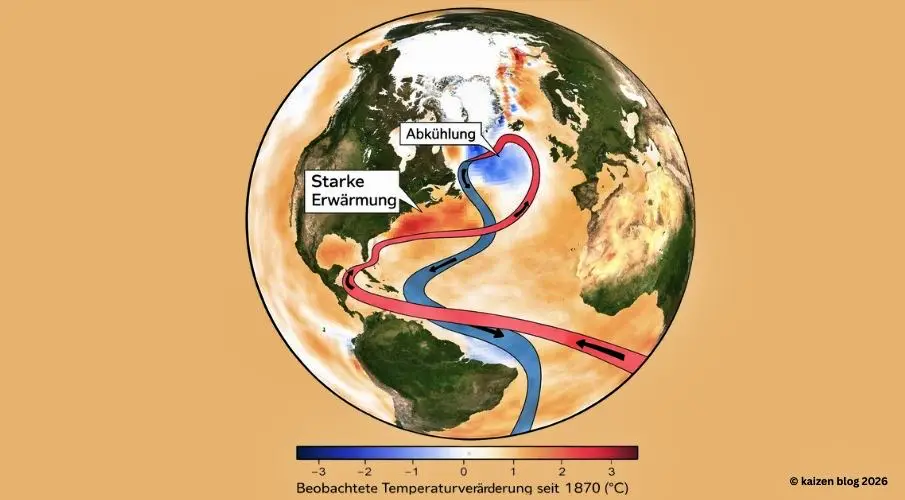

This graphic shows temperature changes since 1870. Red indicates strong warming, blue cooling. The North Atlantic stands out. While large parts of the world are warming significantly, a striking cold patch appears south of Greenland. This is not a contradiction to global warming. It is a warning signal. The red band marks the warm surface current that transports heat from the tropics northward. The blue band represents cold deep water sinking back south. Together they form the Atlantic overturning circulation. It functions like a giant heat pump for Europe and parts of North America.

The blue area in the North Atlantic suggests that this system may be weakening. When melting Greenland ice releases large amounts of fresh water into the Atlantic, surface water becomes lighter. It sinks less effectively. Yet this sinking process is the engine of the circulation. While the world overall warms sharply, part of the North Atlantic could paradoxically become colder - a possible sign of disrupted ocean circulation.

If this weakening intensifies, the consequences would be significant: altered rainfall patterns, harsher winters in Europe, shifts in tropical rain belts, additional strain on already fragile climate systems. Important: this graphic does not prove an imminent collapse. But it shows an ongoing pattern that many researchers have been observing for years.

At the poles, the pace accelerates further. Greenland is currently losing around 30 million tons of ice per hour. The best estimate is that melting could become irreversible at about 1.5 degrees. If the roughly 2.8 quadrillion tons of ice were to enter the oceans entirely, global sea levels would ultimately rise by about 23 feet. The West Antarctic ice sheet is also considered at risk.

In every melt season, countless so called moulins form on the lower part of the Greenland ice sheet - vertical shafts in the ice. Meltwater pours through them deep into the interior of the ice sheet, warming the ice from within and acting like a lubricant that accelerates the sliding of massive ice masses toward the ocean.

Added to this is the potential destabilization of major ocean currents. Particular focus rests on the Atlantic overturning circulation that supplies Europe and the US East Coast with heat. Hansen warns that a collapse within the next two to three decades is possible if warming is not curbed. A 2025 report on global tipping points concludes that failure of this circulation would plunge northwestern Europe into prolonged severe winters. Modeling from Potsdam shows: if temperatures remain above 1.5 degrees through the end of the century, there is a 25 percent probability that at least one global tipping point will be crossed - whether the overturning circulation, the Amazon, Greenland, or West Antarctica. Above two degrees, risks increase further. Domino effects threaten as well: if Greenland melts, it weakens ocean circulation; if that collapses, the Amazon comes under additional pressure.

The world has moved another step toward dangerous warming - but not in the fight against it. In Belém, in the heart of the Amazon, last year’s UN climate conference ended with an outcome that left many delegations stunned. States agreed to provide more money to countries already suffering massively from storms, floods, and droughts. But the central issue that should stand at the core - the phaseout of fossil fuels - is entirely absent from the final document. No clear language, no binding plan, not even the word itself was mentioned.

Despite these warnings, tipping points barely figure in political practice. They are hard to model, hard to quantify, hard to translate into negotiations. At the 2025 climate conference in Belém, UN negotiators for the first time acknowledged that the extent and duration of overshoot must be limited. Concrete measures did not follow. Denmark is so far the only country with an official target for negative emissions and promises a 110 percent reduction compared to 1990 levels by 2050. The discussion of negative emissions is not yet a political project. Afforestation and reforestation could help, but the scale is immense. To lower global temperature by just 0.1 degrees, the IPCC estimates quantities that far exceed today’s natural sink capacity. Some studies speak of 400 billion tons of CO2 that would need to be removed by 2100 to return below 1.5 degrees.

Technical solutions such as direct air capture of CO2 are expensive. Geoengineering approaches, such as injecting sulfur aerosols into the stratosphere to reflect sunlight, are being researched. Britain recently invested 80 million dollars in related studies. Critics warn such measures would not solve the underlying problems. Even if temperatures fall, high greenhouse gas concentrations and altered weather systems remain. Watson compares it to turning on the air conditioning while the house is burning.

Trump’s understanding of environment and climate ends where scientific reality begins

Even moderate climate neutrality targets are currently falling short. And with the withdrawal of the United States as the second largest emitter from the joint project, the international situation has further deteriorated. The warnings of science are unambiguous. Without drastic emission reductions and active removal of CO2 from the atmosphere, a phase of accelerated warming looms that will be barely stoppable. A temporary overshoot could become permanent. Then there would be no turning back.

Updates – Kaizen News Brief

All current curated daily updates can be found in the Kaizen News Brief.

To the Kaizen News Brief In English