The United States has created a system over the past two decades that hardly anyone consciously notices, yet reaches deep into everyday life: a network of cameras, hidden devices, data streams and decisions made far from the places where people are stopped. What was once designed as a tool to combat border-related crime has, under Donald Trump and Kristi Noem, expanded into surveillance that now stretches across entire states. Most affected people only learn about it when they see the lights of a patrol car in their rearview mirror.

Alek Schott from Houston is one of them. Completely ordinary commutes, an overnight stay near the border, a meeting with a colleague – that was all it took for his route to appear as “suspicious” in a federal agency’s databases. He was stopped, detained, his vehicle searched. The officers found nothing. Only later did he learn that his route had previously been digitally recorded and analyzed. A process he never knew was even possible.

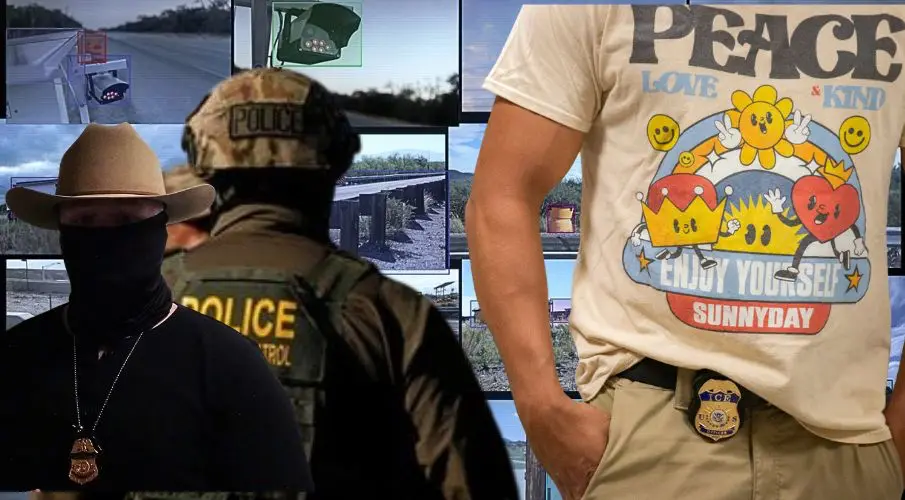

Throughout the South and West of the country, devices now capture license plates and record movement patterns. Some stand openly by the roadside, others are hidden in traffic barrels, construction beacons or disguised boxes at the edges of country roads. At first glance they look insignificant, yet they are connected to a system that tracks millions of vehicles. In Arizona, Texas and California, the surveillance reaches deep into the interior of the country, far beyond the zones officially defined as “border region.” Cameras stand along country roads, in suburbs, at exits of major cities – sometimes more than a hundred miles from the border.

“It is no longer just about getting past the Border Patrol at the border. We are the United States Border Patrol, and we can operate anywhere in the United States of America and enforce immigration law … No one is safe in this country …” says the head of the US Border Patrol. Michael Banks stated on November 13, 2025, that they still record an average of 44 so-called gotaways per day – but that agents are being pulled from the southern border to assist with interior operations. He says they see a decrease in border crossings whenever the agency is involved in a large-scale operation in the country’s interior.

This network has now expanded to include another group: tourists. Anyone traveling in the country for the first time, crossing the Southwest in a rental car or taking a road trip through the national parks, can unknowingly fall into the same patterns. Rental cars are considered particularly “interesting” in many places, spontaneous detours are quickly classified by the algorithms as atypical, and scenic side routes that appeal to travelers for their beauty are viewed in some agencies as an avoidance route. For travelers it is completely harmless, for the system it is a prompt to intervene. No one explains this at the border, no one points it out. Most tourists only realize something is wrong when they end up on the shoulder of the road and officers begin asking questions that do not fit into any travel plan.

The traffic stops usually follow the same pattern. Officially they are about minor issues – a suspected speeding violation, a missing turn signal, a small detail on the windshield. But these justifications are often only a façade. The decision is made earlier: a license camera scans a plate, an algorithm evaluates the route, an officer clicks an internal alert, and shortly afterward a patrol car begins moving. In some cases, the officers conducting the stop do not even know exactly why they are supposed to pull someone over. They receive a license plate, a rough instruction – and act.

The furniture transporter from South Carolina experienced this in drastic fashion. He delivered a shipment to Texas and was detained there. The authorities found nothing – no contraband, no illegal material. Nevertheless, he was arrested, his vehicle impounded, his cash seized. His employer had to spend around twenty thousand dollars just to get his property back. The criminal allegations collapsed once it became clear that everything was based solely on a data set that had flagged an “unusual” route.

Inside the agencies there are chat groups in which sheriffs and Border Patrol agents exchange information. These conversations show how trivial the reasons for a stop often are: a trip to the border region and back, a hotel stay at the wrong time, a brief stop in a parking lot, a late return. It is enough to detain people for extended periods, search their bags, ask questions about personal relationships, check social media profiles or even pass on their home addresses.

What makes this system so difficult to understand is its invisibility. Most cameras are not labeled. There is almost no information about their locations. Even municipalities where they are installed often do not know what the devices are used for. Some states now refuse to release information about them. Others try to hide the role of the Border Patrol in traffic stops by deleting or downplaying references in reports. At the same time, the technical equipment continues to grow: drones, thermal imaging cameras, mobile surveillance units, grant programs that connect local police departments to the network. An agency that traditionally managed physical border security has evolved into an institution that reaches deep into the country’s interior – far beyond what many citizens ever expected.

For Alek Schott, the traffic stop was only the beginning. Only when he began to fight back did he learn how far-reaching the system really is. Today he says that his case only became public because he was not willing to accept what happened to him. Many others, he believes, do not have the time, the resources or the strength to resist. They drive on, irritated or intimidated, without knowing that their route has placed them in a file no one wants to be in. America’s roads have changed. Not visibly, not marked, but clearly noticeable for those who happen to cross the path of a system that no longer observes only the borders. It is a network that operates in the background, expands further and further and whose impact many only understand when it is too late for explanations.

Our investigations will continue, because this is a global problem. Surveillance may make the state’s job easier, but freedom is a precious good. That is what we stand for — and we will not look away. Too many already have.

Updates – Kaizen News Brief

All current curated daily updates can be found in the Kaizen News Brief.

To the Kaizen News Brief In English

Was für eine Zukunft kommt da auf uns zu?

Selbst wenn jeder von diesen Vorgehensweisen wüsste – wer könnt es stoppen?

Wie könnte man es stoppen?

Nicht die Technik an sich ist das einzige Problem, sondern die vielen Zuarbeiter für Weiterleitung und Ausarbeiter dieser Technik sind ebenfalls problematisch.

But wait! Ich sehe die Zukunft – es wird nicht mehr lange dauern und diese Zuarbeiter werden durch noch ausgefeiltere Technik ersetzt.Dann wird der Gang zur Toilette kein persönliches Bedürfnis mehr bleiben – dann wird man der Anzahl dieser Gänge erkennen ob Du gesund bist oder nicht!

Kleine „Scherzfrage“.

Grundsätzlich müsste dieses System demnach auch alle Wege von Beamten und dem Präsidenten registrieren und aufzeichnen.

Wege zur Unzeit, außerhalb der normalen Routen – dürften dann auch für diese Kreise zum Problem werden – sofern man Zugriff auf diese Daten bekommt.

Wie erpressbar wird dieses System durch so ein System?

Diese Überwachung schien schon vor Trump angesetzt zu haben?

Wir unter Trump nur weiter pervertiert?

Wahrscheinlich gibt es weitere Algorithmen, die Konrgessmitarbeiter und Regierungsmitarbeiter inklusive Trump und seiner Entourage, separat aufzeichnen.

Da wird kein Streifenpolizist Zugriff haben.

Das unterliegt dann irgendeiner Geheimhaltungsstufe.

Aber das ist perfekt um alle Bewegungsmuster politischer Gegner aufzuzeigen…

Big brother is watching you 👀

1984 und Minority Report lassen grüßen.

Daten die abseits jeder Kontrolle gesammelt und ausgewertet werden.

Immer mehr von KI.

Ergebnisse werden nicht hinterfragt.

Und all die willfähigen Polizisten, die dabei mitmachen 😞

Eine Freundin von mir, früher auch begeisterte USA Touristin, hat nur Hin- und Rückflug und den Mietwagen gebucht. Den Rest haben sie und ihr Mann spontan entschieden. Meist gezeltet, Hotels selten.

Damit stünde sie heute ganz oben auf der Liste der „suspects“.

Auch wir haben bei unseren USA reisen viele spontane „Umwege“ gemacht.

Auch wenn die Verschärfungen bei der Einreise wohl erst ab Sommer (sicher passend nach der WM) kommen werden, ist diese Überwachung und das Risiko einer Verhaftung hoch.

Zu hoch.

Schade, dass das nicht als Grund für eine Reisewarnung genommen wird.

Es wird kleingeredet.

Lufthansa spricht davon, dass es nicht weniger Buchungen auf US Flügen gibt.

Gruppen für USA Reisen reden es klein und behaupten, dass es nur ganz sdlten Probleme bei der Einreise gäbe und dass diese Leute „selber Schuld seien“.

Es wird krampfhaft versucht, die USA weiter als sicheres Reiseland darzustellen.

Ich liebe die USA.

Die tollen Landschaften, die Weite. Sehr viele freundliche und hilfsbereite Menschen.

Aber in Trumps faschistische USA würde man nicht mal bekommen, wenn man mir eine Luxusreise schenken würde.

#boycottWM2026

..ja eine reisewarnung wäre sinnvoll, dann kann jeder selber entscheiden