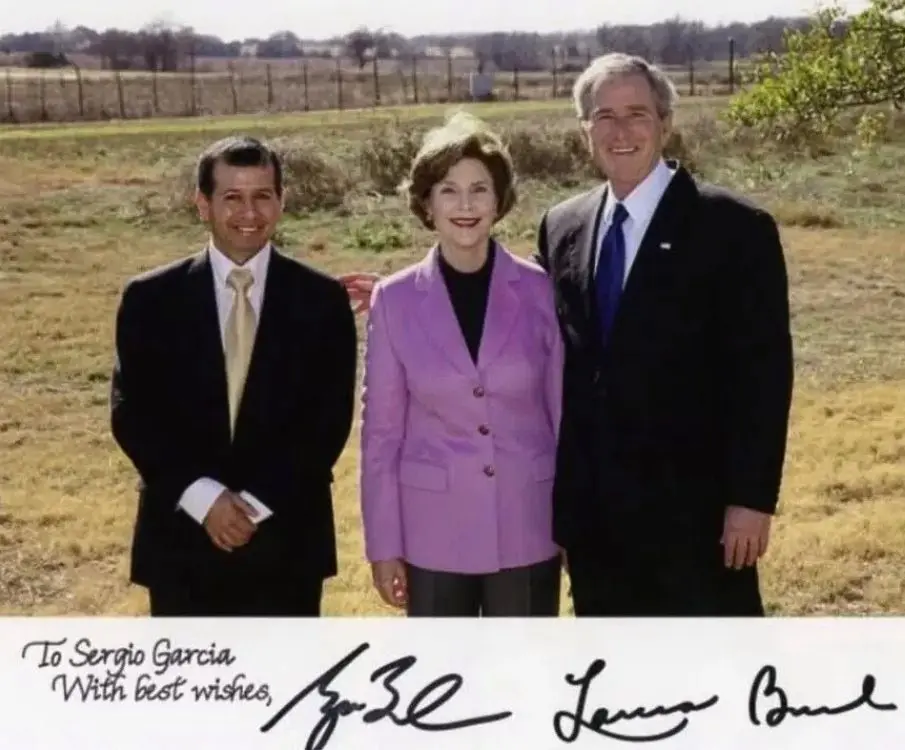

Veracruz/Monterrey/Waco – It was a Tuesday morning in March when the quiet ritual of a workday began in Waco, Texas. Sergio Garcia heated the beans, checked the barbacoa, tasted the rice. For thirty years he had done it that way, with the same dedication, the same calm. Outside, the food truck was waiting, ready for the regular customers downtown. Then two men approached him – one in plain clothes, the other wearing a vest with only one word on it: Police. “They asked if I was Sergio,” Garcia recalls. “I said: Yes, I’m Sergio.” It was the last time he saw his kitchen. Within 24 hours, he was deported across the border to Nuevo Laredo – gone from the country he had enriched for 36 years with his work, his kindness, and his food. Sergio Garcia, born in Veracruz, Mexico, was more than a cook. He was part of Waco – an institution whose ceviche and carnitas attracted even the White House press corps when George W. Bush resided in nearby Crawford. Reporters, senators, security officers – they all knew El Siete Mares, Garcia’s first small restaurant on Dutton Avenue, where plastic chairs became bar stools and warmth mattered more than decor.

When ICE arrested him in March, he had no criminal record, no open cases – only an old, never-enforced deportation order from 2002. For years, authorities had overlooked it. Under President Trump’s second term, immigration lawyers say, that no longer applies. Old files are being reopened, long-integrated families targeted.

For the people of Waco, Sergio was not just one of many. He was the one who helped when someone went broke. The one who let the mechanic use his old restaurant space rent-free so a new shop could start. The man who cooked at weddings and sat in church on Sundays as if he had never left. When news of his deportation spread, dozens of regulars wrote online, cried, donated. “If they can deport him, then it can happen to anyone,” said Stuart Smith, a retired lawyer and friend.

Sergio’s daughter Esmeralda ran the food truck as long as she could. By the end of September, she had to give up. The business no longer paid off, and her father was missing. “Three days after I was born, I was already under the counter in the restaurant,” she says. “My parents always worked. That was their life.” While his family struggled in Texas, Sergio lived through another chapter in Mexico – one that sounds like a nightmare. After his deportation, he was, as he reports, held in Nuevo Laredo by a group that extorted him. They took his phone and threatened to hand him over to “worse people” if he couldn’t find money. For over a month, no one knew where he was. Only when he tried to cross the Rio Grande back into the U.S. was he caught by Border Patrol and deported again – this time first to Veracruz, then to Chiapas, on Mexico’s southern border. Such “deep deportations” (“deportaciones al sur”) are deliberately used by ICE to prevent return attempts.

Sergio was handed over to INM officers at the border and temporarily placed in a so-called “Estación Migratoria” (immigration detention center). There they check identity, create records, and depending on the case, initiate a “controlled release” (liberación controlada) or a transfer to another state.

These facilities are not open camps but closed detention centers – often overcrowded, with miserable conditions. There, deportees sometimes wait days for their release or transfer. ICE describes the same process in cold legal phrases: Sergio Garcia, “a 65-year-old, twice-deported criminal alien,” had “illegally entered the United States in open defiance of our nation’s laws.” No word about what he meant to a city, a community, a country. No mention that he had cooked in churches, catered festivals, and created jobs for decades.

In Waco, they tell his story with a mixture of anger and sadness. Mito Diaz-Espinoza, president of the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, calls it a warning sign: “If they deport someone like Sergio – someone known, loved, and hardworking – then no one is safe anymore.” Since his arrest, many immigrants have avoided public places. Some no longer send their children to school. Fear has returned to a city that once thought of itself as open.

In September, his wife Sandra and his daughter “Esme” published a farewell message to the community. In it, they recalled the story of hard work, resilience, and dreams that had shaped their family. Sergio, they wrote, had grown up in Veracruz by the sea, inspired by the flavors of his homeland. From selling ceviche out of a van to opening his first restaurant, El Siete Mares – his story was one of perseverance, determination, and love for the community.

For more than thirty years, he had poured his heart into serving Waco. People thanked him for being part of their weddings, their Saturday mornings at the farmers market, and the festivals at St. Francis Church. “These memories,” they wrote, “are what made this journey so meaningful.”

But the people of Waco did not want to let this farewell pass quietly. Their reactions to his story were a flood of memory, empathy, and outrage.

“It breaks my heart,” said one woman. “We were going to come in November to show my boyfriend my favorite place.” Another wrote: “I miss you, my brother. I hope you’re doing well.” A former employee remembered: “I’m thankful that working for Sergio was my first job – bussing tables and taking orders at the farmers market.” A regular said: “For two years we lived in Waco, and every Saturday we got a burrito from his food truck. Sandra was always so kind – she remembered our names. I’ll never forget that warmth.”

And then there was a voice that summed up the anger of many: “Beautiful words – but it’s heartbreaking that after 30 years of hard work and love for his community, Sergio is treated this way. ICE – that stands for Institution of Cowardly Enforcement, or simply: Center of Low Dignity. While real criminals roam free, they target a 65-year-old honest, hardworking man loved by thousands, even by former presidents. It’s a disgrace.”

Other people said: “The Garcia family made Waco a better place.” “Your family is a foundation of this city – thank you for all the great food and all the love.” “I hope our country finds compassion again. This should never have happened.” “He was part of us. If they can deport him, it can happen to anyone.”

Amid all the grief, there were also voices of bitterness – people who, with cold logic, asked why he “didn’t become legal after 36 years.” But even that harshness faded under the wave of affection, solidarity, and sadness. Sergio Garcia now lives in Monterrey. He cooks again, on a small scale, for friends, neighbors, and customers who have heard about him. “I’m making ceviche again,” he says. “A few people order, I deliver it. That’s how I started back then.” It sounds calm, almost cheerful – and yet like the beginning of a story he never wanted to end. In Waco, his place is empty. The truck stands still, the logo fades, but his story remains. It lingers in the air like the scent of his kitchen – warm, spicy, honest. And somewhere between the memories, the voices, and the silence stands a question that no one can answer, but that explains everything: Once upon a time in America…

Investigative journalism requires courage, conviction – and your support.

Please help strengthen our journalistic fight against right-wing populism and human rights violations. Every investigative report, every piece of documentation, every day and every night – all of it requires time, research and legal protection. We do not rely on advertising or corporations, but solely on people who make independent journalism possible. People like you.

Not everyone can give the same amount. But everyone can make a difference. Every contribution protects a piece of journalistic independence.

Was für eine nachdenkliche Geschichte.

Wenn man das ganze sieht, eine Tragödie …

Mir fehlen immer öfter die Worte ob dieser himmelschreienden Ungerechtigkeiten, mit der ICE das Land überzieht.

…ja, dieser fall ist sehr, sehr tragisch und zeigt, was in U.S. los ist

Es werden immer mehr integrierte, rechtschaffende und steuernzahlende Menschen abgeschoben.

Einfach damit ICE die Quoten erfüllt.

Natürlich kann man sich fragen, warum er unter Obama oder Biden nicht versucht hat seinen Status zu legalisieren.

Eben weil es diese Abschiebeverfügung gab.

Aber das gibt ICE einfach nicht das Recht ihn ohne Anhörung etc abzuschieben.

Leider sehen die MAGA genau das anders.

Sie bejubeln jede Abschiebung eines illegal eingereisten.

Egal ob derjenige integriert, fleißig und ein wertvolles Mitglied seiner Gemeinde ist.

Da kommen nur kalte Kommentare wie „er hätte ja den legalen Weg gehen können. Selber Schuld“.

Wie kann man nur so menschenverachtend sein?

…ich glaube normale menschen können diese frage gar nicht beantworten