U.S. District Judge James Boasberg has ordered the government to take concrete steps to bring certain Venezuelan migrants, who had been sent to the CECOT maximum security prison in El Salvador, back to the United States at government expense. The ruling strikes at a particularly sensitive point in the current deportation policy: whether the state may remove people from the country without giving them a genuine opportunity to defend themselves before a U.S. court. In March, President Donald Trump invoked the Alien Enemies Act, a wartime statute from the 18th century. On that basis, 137 Venezuelan migrants were classified as alleged members of the gang Tren de Aragua and transferred to the so called Terrorism Confinement Center, or CECOT. The flights departed even though Boasberg had previously ordered orally that the planes be turned around. He later initiated proceedings for possible contempt of court. The conflict between the executive and the judiciary escalated and is now in part before the court of appeals.

Boasberg has now made clear that the government cannot pretend the matter is settled. He sharply criticized the White House for effectively failing to comply with his earlier directive to submit a plan for providing legal process. The government must “correct the error committed here” and create a pathway for those affected to challenge their removal. The order requires authorities to issue so called boarding letters to those men who have since left Venezuela and are currently in third countries. This will allow them to travel back to the United States. The government must cover the cost of the flights. Upon their return they will be detained, but will receive the opportunity to have their removal reviewed in court. Those who remain in Venezuela may also file new briefs. In them, they may challenge both the application of the historic wartime law and their classification as members of Tren de Aragua.

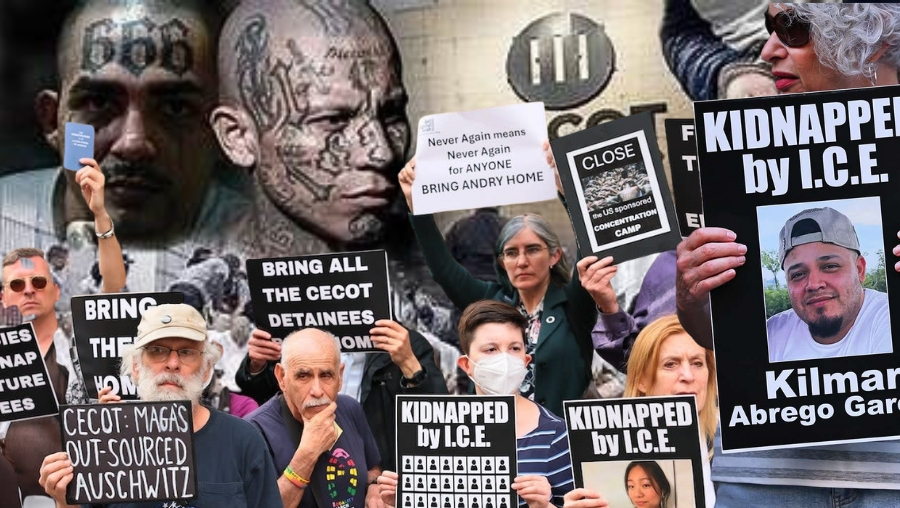

The 137 men were later returned to Venezuela as part of a prisoner exchange brokered by the United States. But that does not change the central legal question: may the government transfer people to a foreign maximum security prison without an individualized hearing and then deny them access to a U.S. court? After months of legal battles and intense pressure, many of those affected were already able to leave the prison in El Salvador. Now the focus is on the remaining cases - on those men who continue to live with the label “gang member” without any U.S. court ever having examined their individual role. Some of them are now outside Venezuela and have indicated that they want to clear their names. How severe the conditions for the detainees were is shown above all by the case of Andry Hernández Romero, who demanded everything from us. In July 2025, Andry was able to be removed from CECOT.

Under the title “The Crownless King” ( https://kaizen-blog.org/en/der-koenig-ohne-krone-the-crownless-king/ ) we first brought the case to public attention, traveled to El Salvador, spoke with relatives, documented prison conditions, and involved both the Immigrant Defenders Law Center and the Human Rights Campaign. What at first seemed like an isolated case turned out to be part of a system: a queer refugee, deported into a torture regime – and instrumentalized by a government that turned human rights into a bargaining chip. Today, months later, Andry Hernández Romero is back with his family. Not in freedom – but alive. And with a voice that no longer remains silent.

Hernández Romero spent four months in the high-security prison CECOT in El Salvador – a place internationally celebrated as a flagship project in the fight against gang violence, yet which for many inmates became a nightmare. For Hernández, as he himself said, it was an encounter with torture and death. He spoke of broken ribs, battered wrists, sexual violence by guards, and days spent in solitary confinement – all of which paint the picture of a system that no longer follows its own rules. In a video message, Hernández described how his tattoos – simple tributes reading “Mom” and “Dad” – were interpreted as proof of alleged membership in the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua. A mistake with a system. And with deadly consequences. What makes this case so explosive is not just the injustice at CECOT, but the path that led there. Donald Trump, back in the White House, invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 – an emergency law originally intended for enemy nations during wartime – to deport over 250 Venezuelans from the U.S. to El Salvador without due process. Hernández Romero, who had been detained under the Biden administration and still had an active asylum application, was sacrificed to this state of legal exception. A politically orchestrated invisibility: no judicial review, no farewell, no protection.

Upon his arrival in Venezuela, he was welcomed by his parents and brother with tears and relief. But there were also others who had been waiting for him – those who held vigils, spread the news, launched petitions. I was never alone, said Hernández, visibly moved. And it is true. From afar, we all fought: lawyers, human rights organizations, journalists. The Immigrant Defenders Law Center, the Human Rights Campaign – they all made the case visible. For HRC, the treatment of queer refugees is no longer a side issue, but a constitutional crisis. The targeted return of people to countries they fled because of their sexual orientation is a violation of international human rights norms. That Hernández Romero can speak again today is more than an individual triumph. It is proof that public attention saves lives. That international solidarity can cross borders – even the walls of a megaprison built to intimidate. That political violence, no matter how technical and sanitized it may appear, must not have the final word. But the story is not over. El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele remains silent on the allegations. The U.S. government refers all inquiries to the Salvadoran authorities. And the Department of Homeland Security simply labels the deported individuals as criminal illegal gang members. But the truth lies in Hernández Romero’s words: It fills me with so much peace, with comfort, with calm – that I was never alone from the first day. That is perhaps the very opposite of isolation. It is what politics cannot destroy: humanity. And if ever there was proof of that, it is Andry Hernández Romero – with his narrow face, his dark eyes, and the clear voice of a survivor. Take care, my friend.

A warning must be issued here: The material from CECOT contained in this article documents extreme forms of human degradation. It is not for the faint of heart - and yet it is an unfiltered mirror of what happens when people are no longer seen as individuals with inalienable dignity, but only as a threat, as a statistic, as a variable to be eliminated in an equation of fear. In Nayib Bukele’s torture hell CECOT - this architectural monument to dehumanization in El Salvador - tens of thousands languish under conditions that mock every civilizational achievement. The partially covertly recorded video footage from this complex shows bodies crammed together, naked figures lined up like cattle before slaughter, people stripped of their individuality and fused into an amorphous mass of misery. This is hell on earth hidden behind the euphemism of “security policy” - a hell operating with the tacit approval, if not the active support, of Washington.

The White House reacted as usual with sharp criticism. A spokesperson described the ruling as “absurd” and accused Boasberg of undermining the lawful powers of the president. Voters elected Trump to deport criminal illegal immigrants and make the country safer; this would not be the final word on the matter. Boasberg, by contrast, argues that if the government’s position were accepted, it could remove people from the United States without granting them any process and then deny them any real opportunity to seek return or a hearing. That, he says, is incompatible with the principles of the rule of law.

The case is therefore far more than a dispute over individual return flights. It stands for the fundamental conflict between deportation policy and procedural guarantees, between executive enforcement and judicial oversight. The decision compels the government, at least in certain cases, to reopen the path back and allow judicial review. Whether this remains an exception or initiates a broader correction will become clear in the coming months.

The struggle will continue day by day. It will continue to demand much from us. But that is no comparison to what the detainees in CECOT have endured. Human rights must have no borders. They apply everywhere or not at all. In Germany as well, an aggressive deportation policy shows troubling tendencies that cannot be dismissed. A society lives from diversity and from cultural exchange. It also lives from the fact that foreign people work, found businesses, lend a hand and keep an economy running. Whoever forgets that weakens not only individuals, but the entire country.

Updates – Kaizen News Brief

All current curated daily updates can be found in the Kaizen News Brief.

To the Kaizen News Brief In English