At the end of December, Saudi fighter jets struck the Yemeni port city of Mukalla. According to Riyadh, the target was a weapons shipment supplied by the United Arab Emirates and intended for the Southern Transitional Council. What had long simmered as a rivalry between Saudi Arabia and the UAE thus turned into an open military confrontation. A new major conflict in the Gulf did not erupt, but the signal was unmistakable. The balance of power among the Arab monarchies is shifting, and with it the order of an entire region. Politically, economically, and strategically, old alliances are coming apart while new fault lines emerge that extend far beyond the Middle East.

The strike on Mukalla was the provisional climax of a rupture that began years earlier. As early as 2015, Saudi Arabia and the Emirates had formed a joint military coalition against the Houthi militias. But at the latest with the gradual withdrawal of the Emirates beginning in 2019, the dynamic changed. Abu Dhabi did withdraw its regular troops, but continued to secure massive influence in southern Yemen through local militias, port facilities, and political networks. The Southern Transitional Council, openly supported by the Emirates, developed into the most powerful force in Aden and the eastern provinces.

Saudi Arabia, by contrast, relied on the Presidential Leadership Council and pursued a different objective: territorial stability and control of strategic corridors. Hadramaut and al Mahra are of central importance to Riyadh. Both regions border Saudi Arabia directly, and al Mahra also offers potential access to the Indian Ocean. For years, the kingdom has planned a pipeline there that would make oil transport independent of the Strait of Hormuz. When the Southern Transitional Council advanced militarily at the end of 2025, closed Aden airport, and openly announced a timetable for the secession of the south, Riyadh saw its security interests directly threatened.

The airstrike on Mukalla was therefore less a tactical intervention than a political demonstration of power. It worked. The Emirates declared the complete withdrawal of their forces from Yemen and avoided a direct confrontation with Saudi Arabia. But the withdrawal was not a withdrawal from the game. Parts of the Southern Transitional Council were brought to Riyadh and declared the dissolution of the organization, but its leader disappeared. His flight, presumably with the support of Emirati forces, shows that Abu Dhabi still has options. Local militias, armed formations, and political networks remain leverage that can be activated again at any time.

The map shows the competition for political and military influence between Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates in the Middle East and parts of Africa. It does not depict formal state alliance borders, but zones of influence – regions in which both states exert decisive influence through military presence, local allies, economic control, or political intervention. The focus is not on official sovereignty, but on de facto power projection.

Diagonally hatched areas mark regions in which Saudi Arabia exercises dominant or significant influence. These include above all Sudan and parts of Yemen, particularly border regions and strategic land corridors. Saudi Arabia pursues primarily security policy objectives here: the protection of its southern flank, control of important land routes, and in the long term access to alternative trade and energy routes intended to reduce dependence on maritime chokepoints.

Also diagonally hatched, but shown separately, are zones of influence of the United Arab Emirates. These include Libya, Somaliland, and parts of southern and eastern Yemen. The Emirati strategy is less expansive than the Saudi one, but far more selective. At its center are ports, coastal areas, sea routes, and logistical hubs, secured through local actors, militias, port projects, or military infrastructure.

Areas marked in yellow are territories in Yemen under the control of pro Iranian Houthi actors. These regions escape the direct influence of both Saudi Arabia and the Emirates and form the core of the ongoing conflict. At the same time, they mark the limit of what external actors can currently enforce militarily or politically.

The competition is particularly evident in Yemen, which appears as the central overlap of both influence strategies. While Saudi Arabia operates there primarily from a security perspective, the Emirates support separatist and local actors, especially in the south and along the coast. Cities such as Aden and Mukalla as well as the provinces of Hadramaut and al Mahra play a key role, as they are of strategic importance both militarily and infrastructurally.

In Africa as well, particularly in Libya and Sudan, the map shows the expansion of this competition. Both countries lack a stable state order, making them preferred arenas of external influence. The power struggle of the Gulf states thus extends onto African territory and affects migration, resource policy, and regional security conditions.

Overall, the map makes clear that this is not a classic proxy war with clear front lines, but a power competition without fixed borders. Influence is not exercised through formal annexation, but through military presence, local allies, economic dependencies, and control over infrastructure and sea routes. This illustrates how fragmented the political order in this region has become – and why conflicts there do not arise in isolation, but are closely interconnected.

The Yemeni theater is only one segment of a much larger competition. Parallel to the events in Mukalla, the Saudi crown prince was in Washington. Officially, the focus was on Sudan, but in the background far more was at stake. The war in Sudan, with millions displaced and a humanitarian catastrophe of historic proportions, has long been part of the power struggle in the Gulf. Saudi Arabia, the Emirates, Egypt, and the United States formally form a mediation framework, but in practice mutual mistrust blocks any serious initiative. Riyadh and Khartoum accuse Abu Dhabi of supporting the Rapid Support Forces. Rumors circulated of demands for US sanctions against the Emirates. Whether true or not, they contributed to escalation.

Beyond Yemen, the rivalry between Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates is also destabilizing. This is particularly evident in Sudan, where a mediation mechanism formed by the United States, Saudi Arabia, the Emirates, and Egypt is effectively blocked. The background consists of mutual accusations: the Sudanese Sovereign Council and Saudi Arabia accuse the Emirates of supporting the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces. In this climate, reports circulated in Washington that the Saudi crown prince had urged President Trump to designate this militia as a terrorist organization and to consider sanctions against the Emirates. Whether accurate or not, such signals intensify tensions and reverberate into other conflicts.

The refugee movements from Sudan cannot be viewed in isolation from the policies of Europe and the United States. For years, Western governments have relied on security based containment, cooperation with authoritarian actors, and outsourcing stabilization to regional power brokers instead of building resilient civilian structures. Under Donald Trump, this line was openly intensified, with diplomacy, development cooperation, and multilateral crisis prevention rolled back. In Europe, right wing populist parties such as the AfD tie directly into this logic. They reject admission, humanitarian responsibility, and long term stabilization, while simultaneously supporting foreign policy approaches that perpetuate or accept instability in regions of origin. The result is a political cycle in which displacement is co produced and then fought as a threat. Migration thus appears not as the consequence of political decisions, but as a domestic political instrument – while structural causes remain untouched.

Added to this is Israel’s recognition of Somaliland at the end of 2025, a step hardly conceivable without consultation with Abu Dhabi. While large parts of the Arab world condemned this, open criticism from the Emirates was absent. The step was geopolitically explosive and difficult to imagine without Emirati backing. Abu Dhabi has economic and military interests in Somaliland, uses the port of Berbera strategically, and systematically expands its influence in the Horn of Africa. The reaction of the Arab world was largely critical, but the Emirates remained conspicuously restrained. Their close cooperation with Israel has long been an independent power factor, regardless of regional sentiment or religious considerations. This development fits into a long term strategy through which Abu Dhabi has expanded its influence from Libya to the Horn of Africa – via ports, security cooperation, and political safe havens. Regional experts largely agree that the withdrawal from Yemen changes little: it marks no strategic shift, but merely a tactical adjustment within a power structure increasingly aimed at controlling maritime access and trade routes.

What separates Saudi Arabia and the Emirates is less the goal than the method. Both want secure sea routes, controlled ports, and reliable regimes. But Riyadh relies more on formal state structures, while Abu Dhabi works more opportunistically with local actors, militias, and separatists. These differences intensify the competition rather than dampen it. At the same time, both countries are competing for economic dominance. The dispute over production quotas within OPEC+, pressure on international companies to relocate their regional headquarters to Riyadh, and the abolition of customs advantages for Emirati free trade zones are expressions of this conflict.

How closely political, economic, and security networks are intertwined became visible beyond formal diplomacy. At a Formula 1 race in December 2019, the then Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman and the then crown prince of Abu Dhabi, Mohammed bin Zayed, appeared together with Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov, who continues to rule the Russian republic of Chechnya, and Russian State Duma deputy Adam Delimkhanov – an image that made visible how international power circles converge in informal spaces.

Competition also unfolds in the air and at sea. Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Doha, and now Riyadh all want to be the central hub between Europe, Asia, and Africa. New airlines, gigantic airport projects, port expansions, and global logistics networks are in direct competition. Behind this lies a strategic realization: oil and gas will lose importance in the long term. Data, transport, artificial intelligence, and media power are intended to form the next foundation of political stability.

Parallel to political and military competition, the power struggle of the Arab monarchies is increasingly shifting into the technological sphere. In Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar, artificial intelligence is viewed as a strategic lever for the post oil and gas era – not only as an economic factor, but as an instrument of long term regime stability. Saudi Arabia has created HUMAIN for this purpose, a state controlled technology company directly subordinate to the crown prince and deliberately modeled on Saudi Aramco, only for data, computing power, and digital infrastructure. The Emirates have gone even further and established the world’s first ministry dedicated to artificial intelligence. At the same time, they are investing in the construction of the large scale data center Stargate, scheduled to become operational in 2026. This technological buildup follows the same logic as earlier energy, port, or media policies: whoever gains control over key technologies secures geopolitical influence, economic dependencies, and political leverage far beyond their own region.

The best airlines of 2025 according to the Skytrax World Airline Awards

Media in particular are a decisive instrument. Qatar demonstrated early how powerful an international news channel can be. Saudi Arabia and the Emirates are now following suit, building their own global media brands and investing heavily in reach, influence, and narratives. At the same time, the lobbying apparatus in Washington is expanding. Billion dollar promises, investment pledges, personal networks, and PR firms are part of a race for attention in the White House and Congress. Trump plays a central role in this. He does not want to lose any side, needs money, loyalty, and strategic commitments. This is precisely what gives the monarchies room to maneuver.

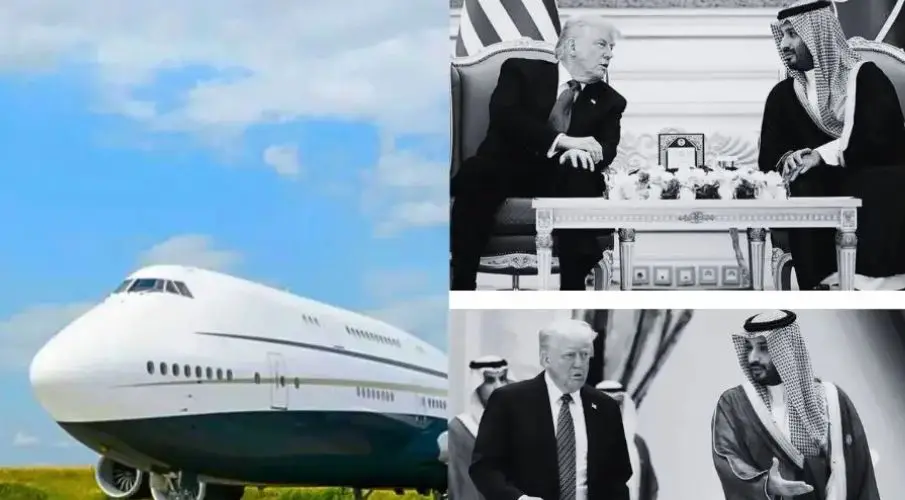

Mohammed bin Salman, the crown prince of Saudi Arabia, together with Donald Trump. In Saudi Arabia, Mohammed bin Salman is not only crown prince and prime minister, but also chairman of all major state development and real estate projects. Anyone who invests there does so under his supervision. And anyone who builds there does so under the eyes of a man whose relationship with Trump has been extremely close for years. While Trump defended the crown prince – for example after the murder of Jamal Khashoggi – business opportunities for his family grew at the same time. In these moments, the roles blur completely. Trump negotiates in Washington over a possible defense agreement that could grant Saudi Arabia far reaching security guarantees. A few days later, he sits with Mohammed bin Salman – a man who is at the same time a key figure in a possible Trump deal. It is a political world in which state visits and private conversations merge, without any attempt to clearly separate the lines.

This is no longer merely about political rhetoric or traditional alliance loyalty. During Trump’s visit to the Gulf, the monarchies outbid each other with investment pledges to the United States. Saudi Arabia initially floated 600 billion dollars, later even one trillion was mentioned. The United Arab Emirates announced projects totaling around 1.4 trillion dollars. Qatar spoke of a further 1.2 trillion. These are, for now, political promises and announcements, not funds already transferred or legally committed. Concrete disbursements on this scale have not occurred to date. But these sums mark the transition from state diplomacy to personalized influence. The competition increasingly focuses on direct, personal access to Trump himself, on gestures, special channels, and demonstrative loyalty beyond institutional procedures. How concrete this development has become was confirmed by the US Air Force in January. A wide body jet donated by Qatar from the ruling family’s fleet is to be ready as an interim solution for Air Force One by the summer of 2026. The aircraft is currently being technically refitted and security checked by the Pentagon. The background is the increasing failures of the more than 35 year old presidential aircraft and further delays in building regular successors. Critics speak of a problematic precedent, because for the first time a foreign state is effectively providing a presidential aircraft while American taxpayers bear the costs of conversion and operation. Trump dismisses the objections and describes the aircraft as a pragmatic interim solution. Politically, this interplay of billion dollar announcements and symbolic proximity exemplifies the race of the Gulf monarchies for influence, loyalty, and privileged access to the presidency.

In this constellation, all available research suggests that Donald Trump understands the presidency less as a public responsibility than as a personal instrument. This impression is not built on insinuation, but on a series of concrete actions: the acceptance of material benefits from abroad that directly benefit the office holder while costs remain with the state; the public linkage of billion dollar investment pledges to his person; demonstrative proximity to his own crypto projects alongside political announcements of deregulation; and the lack of transparency between foreign policy decisions and private business interests. Even security policy issues, such as dealing with Ukraine, are repeatedly personalized by Trump and presented as negotiable variables. He rebuffs critical objections not with institutional arguments, but with the logic of individual benefit – thereby reinforcing the impression that state power is not being administered, but used for personal purposes.

That Europe largely accepts this development without comment appears less like neutrality than passive insulation. Silence politically relieves Trump and contributes to the international consequence free blurring between office, person, and personal advantage. The political and social consequences are devastating.

Meanwhile, the grand vision of a unified anti Iranian front has collapsed. Saudi Arabia has moved closer to Tehran again, Qatar and Oman pursue their own balancing strategies. Only the Emirates maintain a clear axis with Israel. The result is not a new order, but an unstable equilibrium of shifting coalitions. Large scale military conflict is something everyone seeks to avoid, but proxy conflicts, political maneuvering, and economic pressure are increasing.

For the United States, for Europe, and for Russia, pockets of room to maneuver open up – for different reasons – but without stability. Old certainties no longer apply, fixed camps dissolve. Partnerships in the Gulf are situational, interests shift quickly and often against one another. The Gulf is not a political bloc, but a playing field of rival centers of power. Influence can no longer be secured permanently, only through constant balancing, renegotiation, and a willingness to accept losses of power.

Under an AfD led federal government, this logic would likely not weaken, but be openly translated into policy. Such a government would hardly attempt to coordinate European positions or agree on common foreign policy lines. Instead, the focus would be on bilateral arrangements, direct agreements, and autonomous deals. This would particularly affect relations with Gulf states, where independent energy, arms, and investment agreements beyond European coordination would be likely. Consideration for a coherent EU foreign policy would become secondary.

For Germany, this would have tangible consequences. Foreign policy reliability would erode, trust among European partners would wane, and Berlin would lose influence over joint decisions it previously helped shape. Instead of shaping rules, Germany would have to assert itself in a web of individual arrangements in which economic dependencies and political concessions can be more easily played off against each other. In this scenario, the country would lose its role as a corrective within Europe and itself become a participant in that transactional power structure based on personal proximity, economic quid pro quo, and informal networks – with the risk of higher costs, less planning certainty, and a foreign policy vulnerability that would constrain Germany’s room for maneuver in the long term.

What remains is a basic consensus. No one in the region wants open war on their own doorstep. But this is not peace in the classical sense. It is a state of permanent competition, in which territories, resources, media, and political proximity to the White House are constantly redistributed. And precisely here lies the real dynamic of this so called friendship in the Gulf.

Updates – Kaizen News Brief

All current curated daily updates can be found in the Kaizen News Brief.

To the Kaizen News Brief In English

Danke Rainer für diese sehr ausführliche Recherche.

Vieles davon war mir so nicht bewusst bzw gar nicht bekannt.

Dazu wird hier einfach kaum berichtet. Vor allem nicht über diese ganzen verschiedenen Strukturen.

Das Trump gerne was annimmt und sein Amt als Tür für persönliche Deals nutzt, ist leider bichts Neues.

Wo ich mich wundere, dass immer gegen Muslime in den USA gewettert wird, aber wenn Trump mit ihnen klüngelt ist es in Ordnung?

Typische MAGA Hohlbirnen.

Genau, wue die AfD.

Wettern gegen Muslime, aber würden sich persönlich mit Deals bereichern.

Der Nahe Osten wird weiterhin eine große Rolle spielen.

Es bleibt „interessant“, wie die Machtverhältnisse sich entwickeln.

…richtig, aber leider steht das wort „geopolitik“ nicht im europäischen diplomaten-duden, und das wird ihnen auf die füsse fallen …